Often, a child with a special need looks the same as a typically developing child. A great analogy is salt and sugar – they look the same but have very different tastes and cooking properties. Children with disabilities may physically appear to be capable of performing on grade level or achieve social norms; however, they may struggle to follow directions, sit still, or socialize without prompting and guidance.

As a nanny or childcare provider, we can’t assume that every child is equally capable. We need to learn how each child is unique and acknowledge their individual set of abilities and challenges. This is critical as children look to their caregivers for guidance and will learn from their words, actions, and behaviors. Here are 5 strategies to use when caring for all children:

1. Seek to Understand.

Why is the child acting out? Are they misbehaving, not listening, bored, or sick? Perhaps they are overtired, hungry, or are having a difficult time managing the environment. When children struggle, they often don’t know how to express their challenges or ask for help.

If a child is acting out, remember ‘there is a function for every behavior.’ This is particularly important in special education because a child might be acting out because of their disability. For example – you are in line at the grocery store and a child is fidgeting or grabbing all the candy from the shelf. The function for this behavior is likely boredom or a desire for candy, not intentional misbehavior. To help the child, communicate the expectation and find a healthy way to release the energy or provide a distraction. Share that you are not buying any candy and suggest playing a game like Concentration or Eye Spy. If the child is not interested in a game, see if the child can hold several of the grocery items for you, be in charge of the cart, or march in place for 30 seconds without stopping. Solving for the function, in this case, boredom, will help manage the core issue and thus, help the behavior.

2. Communicate Simple and Clear Expectations.

One of the most important things to do when working with a child or a group of children is to set clear expectations at the start. This helps prevent behavioral issues. When giving directions, if a child is defiant or becomes overwhelmed, break the task into smaller steps. Keep directions clear, simple, and concrete. Complete one task at a time and reward children for good behavior and when they accomplish a task.

If a child is defiant and choosing not to listen, calmly communicate the expectation. Then seek to understand the function – do they need a snack or a nap? Try to solve the underlying need. If the bad behavior continues, a behavior chart can be put in place as a means of correcting their behavior through positive reinforcement. By focusing on and providing rewards for good behaviors, the bad behaviors and need to punish should diminish.

3. Structure.

An important structure is a daily schedule. Take a few days in the beginning to learn the rules, expectations, and schedule of activities and tasks. Start each day by reviewing the schedule and expectations using a posted board for the children to see and reference. Take time to practice and perfect these habits with students in the beginning so they understand how to be successful.

It’s also important not to bargain or argue with children, even if they are not happy with the rules. Stay firm in your expectations without being mean by using a calm and consistent tone of voice. After answering the same question two times, staying firm may mean saying, “You’ve asked that question and I’ve already answered it”.

It’s critical that the schedule and expectations stay consistent. If you expect a child to put their plate away, make that expectation clear in the beginning and make sure it is implemented after all snacks and meals. Have a plan. When going to the store, you may reward a child who makes good choices with a snack or their choice of radio songs for the trip home.

4. Breaks.

Sometimes children can have a difficult time focusing and there are a few things that you can do to help.

First, try a movement break. If a child is fidgeting in their seat or having trouble sitting still, suggest they take a one or two-minute movement break. Give the break a specific amount of time and keep some structure in it. Say “Let’s take a two-minute movement break.” Some examples of movement breaks include sprinting, wall sits, pushups, jumping jacks, jump rope, marching in place, or yoga. Another type of movement break for a child is a doodle break. Doodling with crayons or color pencils is a great distractor and a positive way for a child to clear their mind and prevent them from feeling overwhelmed.

Second, change their environment. If you are at a mall or a place with a lot of lights and sounds and a child is crying, anxious, or upset then take them outside for a moment. The child may be experiencing sensory overload. Reducing the information their brain needs to process can help reduce anxiety. If possible, take the child to a place with calming lights and fewer sounds. If in a noisy restaurant, a few minutes in the car may be an environment that helps the child regroup.

Third, teach coping techniques. An example of a coping technique is meditative breathing. You can ask the child to breathe in (count 1,2,3,4) and then breath out (4,3,2,1) and repeating. Another technique is to have the child tap their fingers together (bringing the thumb to meet each of their other fingers on the same hand.) This is known as finger tapping and can be incredibly helpful in calming children.

Fourth, use fidget or sensory toys. Whether you are taking a child out for errands, in a waiting room, or driving in a car, a child with sensory issues or impulsivity and hyperactivity may struggle to remain still. In these instances, it might be handy to carry some fidget toys around with you. If you are pushing a child in a shopping cart and they are fidgety, give them a fidget toy to use. If you are waiting for a doctor’s appointment, have some putty on hand with a few small toys to hide inside.

Children struggling with disabilities may use these strategies, but they may require and need additional supports depending on the severity of their disability. In my experience, I have had students who would take one break a day and others who would need to take 10-15 breaks a day. It all depends on that individual child’s needs.

5. Organization.

5. Organization.

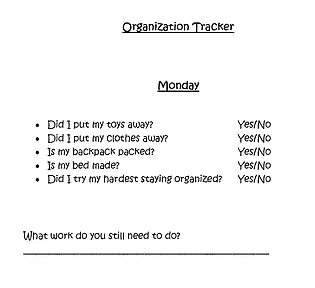

Organizational difficulties are common as some students have a difficult time keeping both their mind and their belongings organized. By providing children with structure, prompting reminders, and guidance, you can help them to stay organized. Let’s use a messy bedroom as an example. To help, label bins and hooks as well as have clearly defined spaces in the closet for items. When the children are cleaning up, minimize the distractions and provide redirection and reminders.

For a student that is really struggling with organization, you can create a reward system. For example, if their backpack is organized and all papers are put away in the correct place they can receive a prize from the prize bucket. A prize bucket is a bucket that you fill with low-cost toys and items. This sort of incentive can be very motivating for some children.

When helping children who might be struggling with organization issues, it is important that you provide proper guidance, support, and prompting. Remember, a child with a messy room isn’t necessarily being lazy – they may just need some guidance and direction on where they should begin and prompting on which items to put away.

There are so many things you can do that can help a child struggling with their disability. It is the childcare provider’s role to figure out what is causing the child’s behavior and help manage it. Children generally don’t have the language and ability to express how their disability is affecting them at any given time, so do your best in your observations and respond accordingly.

For more information about caring for children with disabilities, a Special Education course is available within the Specialist Childcare Certification Program from the Nanny Institute.

About the Author. Kerri Beisner earned a Master of Education in Moderate Learning Disabilities K-8 and is a special education teacher in Connecticut. Kerri is volunteers with the Special Olympics and has authored the children’s book, The Nightluns Stone. Kerri is also an adjunct faculty member of the Nanny Institute, an organization dedicated to professional nanny training and certification of elite nannies, au pairs, sitters, and other childcare providers.

Recent Comments